Hello, I’m Kate Farrell, author of the Fairy Tale Heroine, your guide as we explore the hidden terrain of the feminine quest. The narrative circle of the heroine’s journey goes in just the opposite direction from the hero’s journey: it’s the other side of the same coin.

There are three basic stages in the heroine’s journey:

· One—Entanglements and Jealousies

· Two—Escape and Initiation

· Three—Return and Recognition

This Slavic tale of “Baba Yaga and Vasilisa” is an excellent example of the heroine’s return since it depicts not only her return from the treacherous forest to her home, but also her return to the village and community.

Recognition is a big part of the fairy tale heroine’s ending: being seen publicly for who she is. In this tale, Vasilisa finds a mentor who supports her work and facilitates her in being seen, elevating her status in the community as a leader.

In Episode Four, we ended the tale just as Vasilisa completed the second task demanded by Baba Yaga, the sorting of the seeds with the help of the mice. Baba Yaga is not pleased and seeks an answer.

“Baba Yaga and Vasilisa”

"Have you done what I told you to do, Vasilisa?" Baba Yaga asked.

“Yes, it's all done, Grandma.”

Now I’ll ask you something. How is it you manage to do the work I set you to do?” Baba Yaga asked.

“My dead mother’s blessing helps me,” replied Vasilisa.

“Eh! eh! what’s that? Get along out of my house, you bless’d daughter. I don’t want bless’d people.”

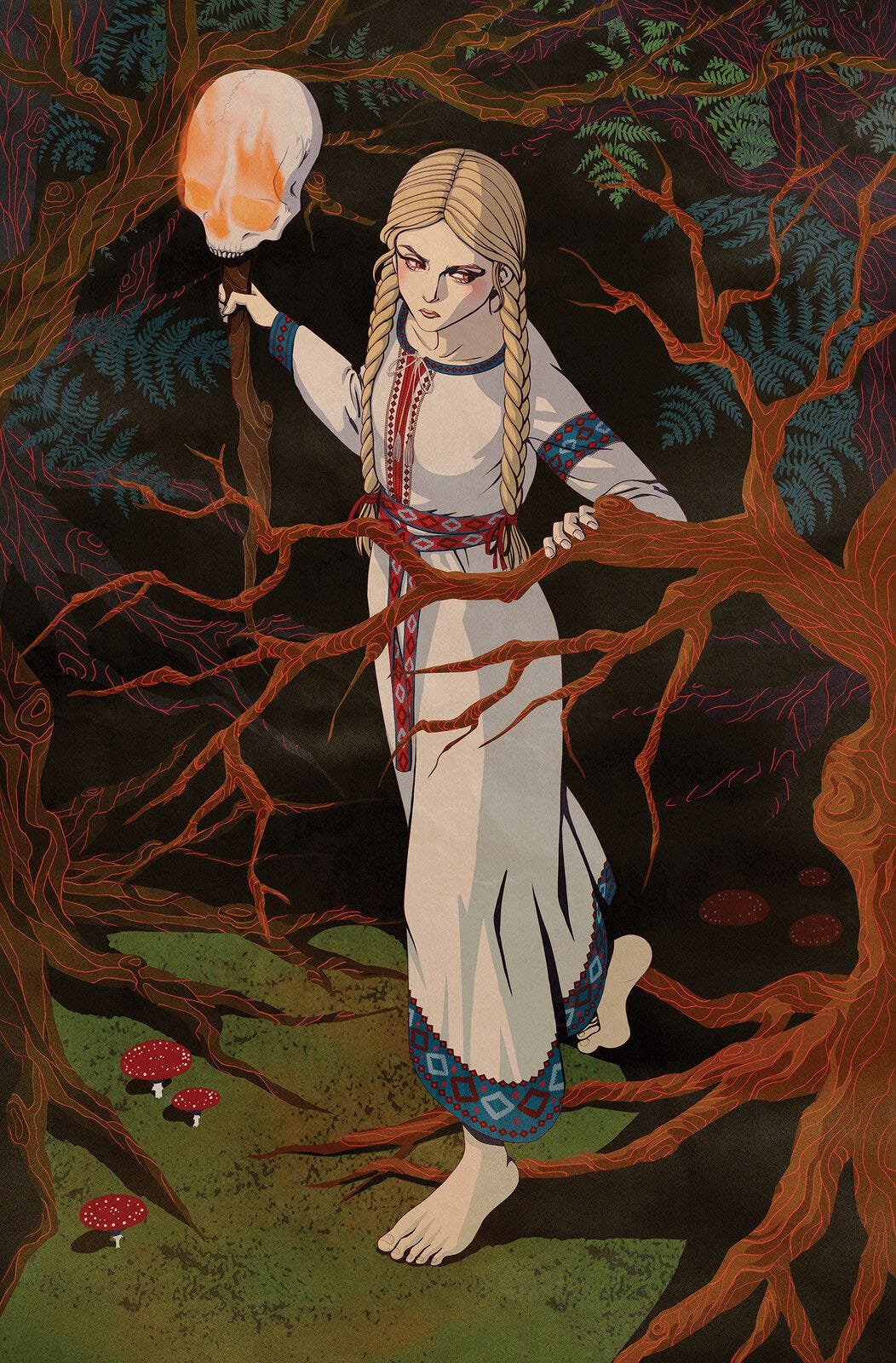

She dragged Vasilisa out of the room, pushed her outside the gates, took one of the skulls with blazing eyes from the fence, stuck it on a stick, gave it to her and said, “Lay hold of that. It’s a light you can take to your nasty stepmother. That’s why she sent you here, I believe.”

Vasilisa ran into the dark forest, and it was pitch black all around. But the eyes of the skull glowed until it was as light as day. She ran home, and as she came closer, she saw that there was no light in the hut.

Her stepsisters rushed out and began to chide and scold her. "What took you so long fetching the light? We cannot seem to keep one on in the house at all. We have tried to strike a light again and again but to no avail, and the one we got from the neighbors went out the moment it was brought in. Perhaps yours will keep burning."

They brought the skull into the hut, and its eyes fixed on the stepmother and her two daughters and burnt them like fire. They tried to hide, but run where they would, the eyes followed them and never let them out of their sight.

By morning they were burnt to a cinder, all three, and only Vasilisa remained unharmed.

She buried the skull outside the hut, and a bush of red roses grew up on the spot.

After that, not liking to stay in the hut any longer, Vasilisa went into the village and made her home in the house of an old woman.

One day she said to the old woman: "I am bored sitting around doing nothing, Grandma. Buy me some flax, the best you can find."

The old woman bought her some flax, and Vasilisa set to spinning yarn. She worked quickly and well, the spinning-wheel humming and the golden thread coming out as even and thin as a hair. She began to weave cloth, and it turned out so fine that it could be passed through the eye of a needle, like a thread. She bleached the cloth, and it came out whiter than snow.

"Here, Grandma," said she, "go and sell the cloth and take the money for yourself."

The old woman looked at the cloth and gasped. “No, my child, such cloth is only fit for a Tsarevich to wear. I had better take it to the palace."

She took the cloth to the palace, and when the Tsarevich saw it, he was filled with wonder.

"How much do you want for it?" he asked.

"This cloth is too fine to be sold, I have brought it to you for a present."

The Tsarevich thanked the old woman, showered her with gifts and sent her home.

But he could not find anyone to make him a shirt out of the cloth, for the workmanship had to be as fine as the fabric. So he sent for the old woman again and said: "You wove this fine cloth, so you must know how to make a shirt of it."

"It was not I that spun the yarn or wove the cloth, Tsarevich, but a maid named Vasilisa."

"Well, then, let her make me a shirt."

The old woman went home, and she told Vasilisa all about it. Vasilisa made two shirts, embroidered them with silken threads, studded them with large, round pearls and gave them to the old woman to take to the palace. By and by one of the Tsar's servants came running toward Vasilisa.

"The Tsarevich bids you come to the palace," said the servant.

Vasilisa went to the palace and, seeing her, the Tsarevich was smitten with her beauty.

"I cannot bear to let you go away again; you shall be my wife," said he. He took both her hands in his and he placed her in the seat beside his own.

And so Vasilisa and the Tsarevich were married, and, when Vasilisa's father returned soon afterwards, he made his home in the palace with them. Vasilisa took the old woman to live with her too, and, as for her little doll, she always carried it in her pocket.

And thus are they living to this very day, waiting for us to come and stay.

Reflections

What does the skull represent, as Vasilisa returns with it held high, lighting her way to the hut where her stepsisters and stepmother live? What is the source of the skull’s destructive power?

What is the old women’s role in the village: mentor? ally? an independent woman of attainment?

What specific part does the Tsarevich play at the end of the tale?

How does this Slavic tale compare to other versions of “Cinderella?” How does Vasilisa demonstrate her agency as a heroine?

My Personal Story: Return and Recognition

Library Graduate School, UC-Berkeley, 1970

Student skirmishes and demonstrations against the war in Vietnam were part of life at UC-Berkeley, with frequent exposure to tear gas or the sudden surprise of a hidden contingent of a riot squad along a secluded path. But when President Nixon announced the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, May 1, 1970, the war escalated and so did student protests. Our outrage was visceral and immediate: College students across the country walked out and went on strike, including us scholarly, library school students.

When the strike was followed by the Kent State student massacre at the hands of the Ohio National Guard, May 4th, we mourned and mobilized to act. Wearing black arm bands, we met in the Victorian lecture hall on the second floor of venerable South Hall and took a winning vote: to cancel all classes and plan non-violent responses appropriate to the library profession.

Because the four of us, my brilliant friends and I, were outspoken with creative ideas, identifiable as a nucleus, we were called by some library students, “the four horsemen.” This was in-house satire, a supposed compliment to our ready stance to meet the challenges of participating in the student protests, as in the Bible’s Book of Revelations: the Four Horsemen who rode out on white, red, black, and pale horses.

After our Master's Degree graduation with no official ceremony given the political chaos, a Bay Area librarians’ professional group invited the four of us to speak on a panel at their annual dinner held at a swank, Japantown restaurant in San Francisco. Each one of us "horsemen" in turn described her contribution during the strike and its aftermath.

In the Q&A, there was a pointed question: "How will these radical experiences affect your career as a librarian?" Another gauntlet thrown—one that would motivate me in the unseen, endangered future of library services.

Reflections

Taking a public stand during an historic time can be daunting. How did my actions create recognition? How did they validate and motivate me?

Our student group made lasting changes to the UC-B Library School program, to refocus it on serving the community with the library as a living forum. How was that an heroic return?

Was there a time in your life when you became a leader among peers? What did this cause you to recognize within yourself?

Kate is the founder of Woven: Telling the Heroine’s Journey based on her work with storytelling, finding profound meaning in the archetypes of feminine fairy tales. She shares her process in workshops and on Substack. Her new book, The Fairy Tale Heroine: Live and Create Her Journey, is available in Winter 2027 from Sibylline Press!

Share this post