The Fairy Tale Heroine: Live and Create Her Journey

Chapter One: Part III

A battle between the Hero v. Heroine is playing out in the United States since the presidential election. The hyper-masculine qualities in the picks for the incoming Cabinet are evident as they portray arrogance, self-claimed authority, and alleged ethical violations against women and boys. The few women nominated, such as for Secretaries of Education and Homeland Security, have the combative stance of a masculine hero in the co-founder of World Wrestling Entertainment or in the gun advocate who voted against women’s rights and against the Violence Against Women’s Act. There is no question that women rights are a target, along with the roughshod, free rein willfulness that will attack basic services of the federal government that serve the common good.

We cannot afford to lose ground in this fight, but continue to draw strength from the archetypes of the feminine quest, the heroine’s path to independence.

Inner Journey Is Vital

Under the surface in our culture, the fairy tale heroine can become our steadfast fellow traveler. Her journey is a coming of age story that repeats throughout the lives of women today—as we continue to “come of age” in each phase of our lives. Her tales operate in a multi-dimensional space within the symbolic language of archetypes that exist in our unconscious; her issues continue to be our issues.

In feminine fairy tales the heroine is alone, faced with daunting challenges that resonate in our time.

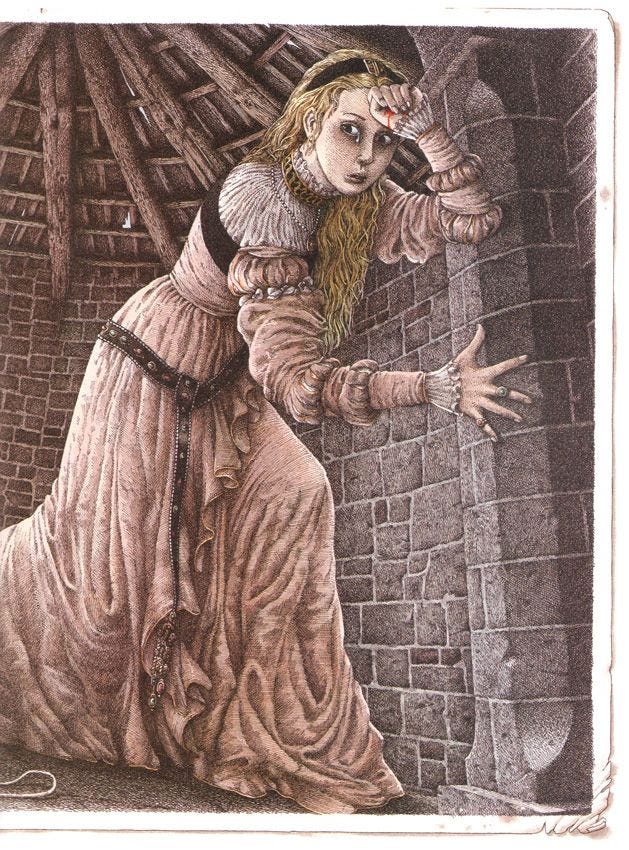

One extreme example of this trope is Rapunzel in her tower, isolated from all help or contact, trapped, the walls closing in on her with only a single window open to the world. We can relate to the restrictions of the feminine in modern culture, the overwhelming task of breaking out, cracking the glass ceiling to escape confinement of the Self. For Rapunzel, it is through her voice, a self-expression of inner beauty so clearly true that she is heard throughout the land, her authenticity recognized as she sings from her high window.

If we look at feminine fairy tales anew—through the lens of our own psychology—we can see ourselves in Rapunzel. Furthermore, we see her struggles taking place in the feminine realm: a mother whose needs were more important or demanding than her daughter’s and a witch, a dark, jealous, vengeful aspect of the feminine psyche.

No, these stories were not meant for children, but as pathways, guideposts to full feminine development. We can sense these ancient fairy tales living within us if we listen carefully, and then realize how different they are from the myths of the hero’s journey.

The Hero and the Heroine: Their Journeys

Though the legendary journeys of the hero and the heroine are different, they do not lead to separate destinations: one begins where the other one ends. They are but two sides of the same coin—that golden coin of the realm, possession of self fulfillment and wholeness. As indicated previously, masculine and feminine journeys are not limited by gender or sexual orientation. Ideally, we would all experience both, developing male and female aspects within our personalities throughout our lives in a unique balance, adaptable, flexible, an individual androgyny.

It is only lately, in modern Western history, that our culture has become male dominated, gradually over many centuries, accelerated in the last few. In the Middle Ages, the world was thought to be flat. Today our one-sided psyche is flat and we may literally fall off the edge of the Earth. Due to the prevalence of man over nature and the level of denial in climate change, male aggression will deplete the planet while encouraging overpopulation and female reproduction.

It’s a doomsday scenario, one that rejects eco-feminism, a view of the world that values organic processes, holistic connections, intuition, and collaboration. The competitive exploitation and degradation of the natural world can lead to the subordination and oppression of women. Co-existing male and female energies, achieving their balance within our culture, are linked to our very survival.

The early tales, myths, and legends are stories that depict ways of becoming whole. In the pre-literate days of the oral tradition, the “folk” were more connected to dreams and a naïve sensibility. They were people who actually listened to birds and to whispers in the trees, who lived in a multi-dimensional, animated, fluid world that spoke to them. Without access to written literature, their tales became a cultural depository, held sustaining values, a sense of consequences to action, innate justice, and figurative layers of thought.

In this honored, literary heritage, folk and fairy tales continued to be its core expression down through the generations.

The 18th and 19th century scholars and collectors revered the literature of the folk as authentic and of great cultural value, an immense body of literature as wide and deep as the sea, expansive and inclusive, worthy of careful preservation and classification. In the early 20th century, Jung and others found fairy tales a pure expression of the psyche, representing archetypes in their most concise form and by contrast, considered myths or legends to be filtered with an overlay of cultural material.

Yet those who now promote the hero’s journey reject fairy tales in favor of myths and legends in order to create a masculine monomyth.

The Monomyth

We are most familiar with the hero’s journey made popular by Joseph Campbell and made practical for writers by Christopher Vogler, leading to its profound impact on modern storytelling in film, video games, and fiction. Campbell’s classic book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949, 1972, 2008), traced various mythologies of the hero’s journey to reveal one archetypal hero and one seminal plot line or monomyth.

Campbell discounted fairy tales— he said that he wanted to include “female heroes” in his work, but discovered that he had to go to fairy tales to find them: “These were told by women to children, you know, and you get a different perspective.” He claimed that “all the great mythologies and much of the mythic storytelling of the world are from the male point of view.” Campbell knew in his research of females who undertook quests with difficult tasks and cited the tale, “Psyche and Eros.” But he dismissed it as an anomaly in which the principal characters were in reverse—supposedly since the female seeks and rescues the male.

But by disdaining the entire literary catalogue of fairy tales as inferior to myths due to an assumed feminine perspective, Campbell essentially erased the heroine’s journey from his literary world view.

Truly, tales of the feminine quest, suppressed for millennia, rarely achieved the elevated status of epic legends or myths, not since the first Sumerian epic poem, “The Descent of Inanna,” written on clay tablets in the third millennium BCE. The heroine’s journey survived in the oral tradition as fairy tales. However, even those tales of the heroine were suppressed, fragmented, and devolved into sanitized or Disneyfied versions featuring weakened female characters with little or no agency, even cartoonish figures.

Christopher Vogler wrote in The Writers Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers (25th anniversary edition, 2020): “For good or bad, hero stories now dominate the world’s narrative entertainment through games and big-budget epic superhero franchises.” While a story analyst for Walt Disney, when Vogler was asked to review major fairy tales of world cultures looking for animation subjects, he referred to the tales as children’s literature in his new edition’s chapter, “Stories Are Alive.”

Classic fairy tales gave him pause as he ruminated about their meaning and cultural value, not aware of the depth of existing analysis about the tales. He puzzled about them, not able to break their “story code.” As a film student at the University of Southern California, Vogler had discovered that “Campbell had broken the secret code of story” with the hero’s journey model.

Obviously, Vogler needs a new guide, since all the tales he mentions in the chapter are examples of the heroine’s journey: “Cinderella,” “Snow White,” “Sleeping Beauty,” “Rapunzel,” and “Rumpelstiltskin.”

In his retelling of “Rumpelstiltskin” with an odd commentary from the male perspective of the “little man,” Vogel suggests his motivations, even that the manikin might be the father of the maid’s child whom he wishes to kidnap at the baby’s birth—a complete reversal of the heroine’s tale of triumph into a hero’s tale of greed and desire.

In fact, Vogel implies that the maid might be the victim of sexual assault or rape. He writes, “After all, what is there to do in an empty room for three nights when all the straw has been spun into gold?”

Vogel has clearly lost his way in understanding the tale of the feminine quest by displacing the heroine’s role entirely, even to the point of imagining her sexual abuse by Rumpelstiltskin who might have every right to claim his own infant.

This distorted view of feminine fairy tales by an erstwhile Disney story analyst is alarming. It is evidence that male potency extends to popular movies for young girls, animated fairy tales produced by men.

My view of the famous tale* in which a poor miller makes an empty boast to the king that his daughter can spin gold from straw, and so places the maid’s life in danger as the king seeks to make her prove it or die, is that the maid finds a way to succeed. The “manikin” who magically appears in a locked room of the castle filled with straw to spin into gold, represents her unknown strength born of desperation. When the maid, now queen, eventually names him, she owns him and her own inner power.

It is critical that women today prove their worth in gold and name their power.

###To be continued

PROMPTS

Do you find Vogel’s interpretation of “Rumpelstiltskin” offensive?

What do you think this fairy tale of “spinning straw into gold” means?

What is your super power?

*Link to a Grimms’ version of the ancient tale of Rumpelstiltskin:

https://www.grimmstories.com/en/grimm_fairy-tales/rumpelstiltskin

Note: According to researchers at Durham University and the NOVA University Lisbon, the origins of the story can be traced to around 4,000 years ago. A possible early literary reference to the tale appears in Dionysius of Halicarnassus's Roman Antiquities, 1st century CE. The same story pattern occurs around the world, ATU 500: “Naming the Supernatural Helper."

Kate, I know we all think of Joseph Campbell's classic work as "timeless," but it isn't. He was born in 1904, into an Irish-Catholic family. No wonder he had such a difficult time hearing strong female voices. You always give me something new to think about. Thank you!