The Fairy Tale Heroine: Live and Create Her Journey

Chapter Four: Escape, Part I

Snow White ran for her life through the forest near the castle, stumbling on the uneven terrain, tripping on tree roots, past wild animals, not daring to stop—she ran on and on with sore feet and torn clothes until it grew dark.

This is the moment of flight in the fairy tale heroine’s journey; she must escape or die to herself.

It is the transition from the first stage, that of entanglement with toxic relationships, restrictions, and exploitation, to the second stage of initiation in the wilderness. Hers is a dramatic departure, on the run, a free fall into the unknown.

Breaking away from uniquely feminine snares is essential for the heroine’s path to continue, whether it is separating from the “wounded mother,” or the destructive jealousy of peers, or simply from the limiting constraints of conventional expectations. In the fairy tales, her escape is a risk-taking, absolute break from which there is no return.

The heroine flees into the wilds.

Though the archetypal imagery of the fairy tales is extreme, death-defying, it can echo a resonating emotion in the lives of modern women. We might not be traversing a forest inhabited by wild creatures, but we could be driving alone from Ohio to California with no plans or friends to greet us. The key dynamic is a clear breakthrough from confinement to personal freedom—to an undetermined self-initiation.

The fairy tale heroine, far from the passive, sweet princess of Disneyfied picture books and movies, has agency, takes risks, escapes her own prison or tower to an undefined place, off the map, do or die. In many ways, the feminine heroic is even more courageous than the masculine’s since her story has been suppressed for millennia without a clear pathway to follow: no predictable fire-breathing dragons around the corner. She follows without knowing the nature of her trials ahead.

But there is no turning back, as this excerpt from “Snow White” clearly shows:

One day when the queen asked her mirror:

Mirror, mirror, on the wall,

Who in this land is fairest of all?

It answered:

You, my queen, are fair; it is true.

But Snow-White is a thousand times fairer than you.

The queen took fright and turned yellow and green with envy. From that hour on whenever she looked at Snow-White her heart turned over inside her body, so great was her hatred for the girl. The envy and pride grew ever greater, like a weed in her heart, until she had no peace day and night.

Then she summoned a huntsman and said to him, "Take Snow-White out into the woods. I never want to see her again. Kill her, and as proof that she is dead bring her lungs and her liver back to me."

The huntsman obeyed and took Snow-White into the woods. He took out his hunting knife and was about to stab it into her innocent heart when she began to cry, saying, "Oh, dear huntsman, let me live. I will run into the wild woods and never come back."

Because she was so beautiful the huntsman took pity on her, and he said, "Run away, you poor child." He thought, "The wild animals will soon devour you anyway," but still it was as if a stone had fallen from his heart, for he would not have to kill her.

The poor child was now all alone in the great forest, and she was so afraid that she just looked at all the leaves on the trees and did not know what to do. Then she began to run. She ran over sharp stones and through thorns, and wild animals jumped at her, but they did her no harm.

She ran as far as her feet could carry her, and just as evening was about to fall she saw a little house and went inside in order to rest.

###

Heroic Moment of Escape

In the hostile fairy tale environment of an orphan maid with a wicked stepmother and ugly stepsisters, with an absent, neglectful father, there is no other option than to flee. Interpreted within female psychology it is the entrapment of relationships with their expectations, the odious comparisons, jealousy and vanities, the lack of self-definition and independence, that are fatal. Remaining, living inside these restrictions is one choice, but it is not the heroic one.

It is in leaving that the feminine will discover personal power: The environment of the “wilds” is an unknown place beyond cultural conformity, a brush with her origin and primal knowing, the wisdom of the feminine.

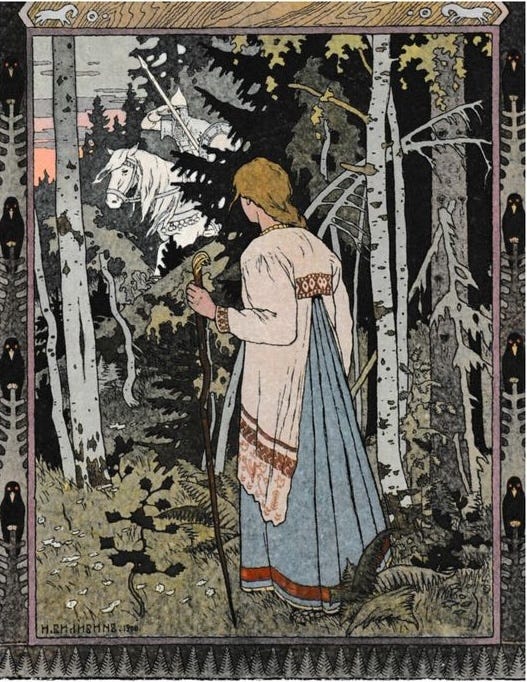

As you read this excerpt from “Baba Yaga and Vasilisa,” walk with the maid in the forest, through one night and one day; experience what she encounters and how she finds her courage:

The blackness of night was about her, and the dense forest, and the wild wind. Vasilisa was frightened; she burst into tears and she took out her little doll from her pocket.

"O my dear little doll," she said between sobs, "they are sending me to Baba-Yaga's house for a light, and I’m so afraid."

"Never you mind," the doll replied, "you'll be all right. Nothing bad can happen to you while I'm with you."

"Thank you for comforting me, little doll," said Vasilisa, and she set off on her way.

About her the forest rose like a wall and, in the sky above, there was no sign of the bright crescent moon and not a star shone. Vasilisa walked along trembling and holding the little doll close all night.

All of a sudden whom should she see but a man on horseback galloping past. He was clad all in white, his horse was white and the horse's harness was of silver and gleamed white in the darkness. It was dawning now, and Vasilisa trudged on, stumbling and stubbing her toes against tree roots and stumps. Drops of dew glistened on her long plait of hair and her hands were cold and numb.

Suddenly another horseman came galloping by. He was dressed in red, his horse was red and the horse's harness was red too. The sun rose, it kissed Vasilisa and warmed her and dried the dew on her hair.

Vasilisa never stopped but walked on for a whole day, and it was getting on toward evening when she came out on to a small glade.

###

As Vasilisa traverses the unknown, the dangerous wilds of the forest, she takes comfort and strength from the talisman given to her by her loving mother. She does not question it, but finds absolute confidence in the doll’s advice—an attribute not considered inborn for the feminine. She persists and does not stop, but keeps walking steadily through night and day until she comes to a clearing at dusk.

The steadiness of Vasilisa is remarkable, though she trembles through the dark of night without moonlight or starlight to guide her. The dense forest closes in around her like a wall on either side: she cannot see or know her way. This is the courage and the perplexity of women in that we have lost our way to the wise Crone of the wild forest. Her place in our culture has been denied so completely that that we can only keep going to find her with a primal instinct, holding on to the little doll who represents the feminine archetype of instinct, intuition, and wisdom, our ancestral legacy.

Twice, frightening large beasts gallop past Vasilisa: a white horse and rider who brings the dawn and a red horse and rider who cause the sun to rise. We imagine that Vasilisa notices them, yet continues to walk ceaselessly through the entire day.

Vasilisa’s attitude is similar to Snow White’s progression through the forest, running, stumbling, without pause until she comes to a clearing with a small house in the evening. They both encounter strange creatures that, nevertheless, do not harm them. It is as if their very will power protects them in their quests. In this surreal wilderness, they come into their own sense of self by their relentless walking, running away.

The heroines are escaping those environments and people that would do them harm or prevent them from expressing their essential nature.

We often imagine that women only flee from a husband’s or male partner’s domestic violence, but her escape from negative feminine aspects is the heroine’s essential work before encountering a potential male or intimate partner. If she is able to separate from the “wicked mothers” and “ugly sisters” early in her maturing process, she might be spared further negative, intimate entanglements.

The heroine is steadfast in running towards herself.

My Escape Story

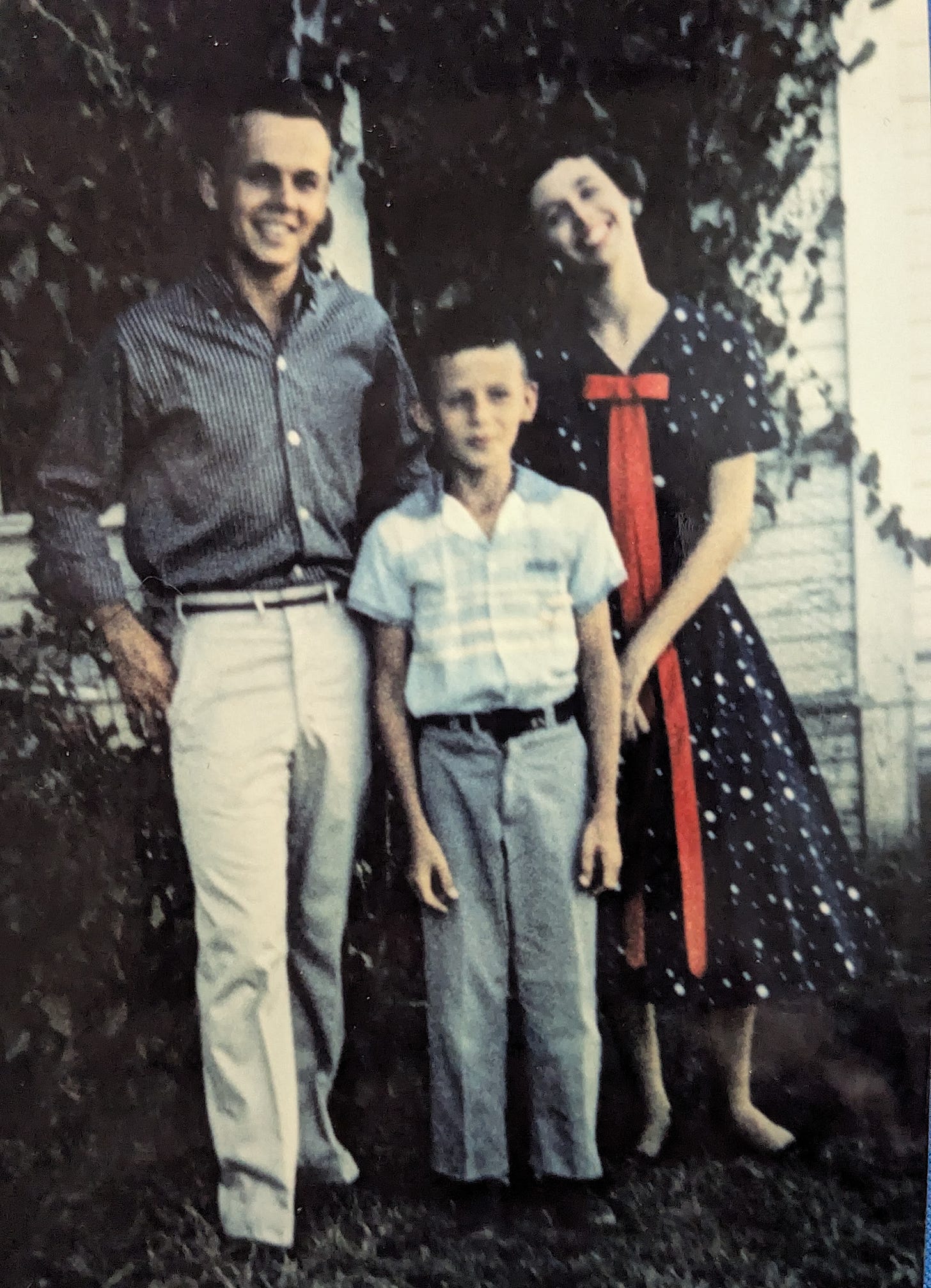

In which I escape my abusive childhood home, neglectful and cruel, where my mother was a stand in stepmother, my father absent and distant, my older brother resentful, my younger brother in need. I yearned to leave and attend college “up North.”

In May 1959, when I graduated from high school in San Antonio, Texas, I'd opened many greeting cards and letters from distant relatives, cousins, aunts and uncles I'd barely met, grandmothers and great aunts, sometimes with a five or ten dollar bill enclosed, congratulating me. I did graduate in the top ten of my class and received a scholarship to attend Our Lady of the Lake, a local Catholic college for women.

Never did I expect a letter from my great aunt, Sister Georgina, on my mother's side, encouraging me to apply to Rosary College, a highly respected liberal arts college run by a Dominican order of nuns near Chicago, offering to sponsor me.

Energized by the surprising opportunity to attend college "up North," that accepted my application, I combined my cash gifts into the huge sum of one hundred dollars and launched a summer project to design and sew a collegiate wardrobe.

All my life, my mother had sewn frilly dresses for me, like a living doll in her image. It was the only connection we really had: I was a vicarious projection of her desire to be young and attractive. My mother never complimented my looks, only how I looked in the clothes she’d designed.

Nevertheless, I'd become quite the seamstress in my teen years, mentored by Mom and in Home Ec class at school. From the many date and dance dresses we'd sewn, I knew the drill: Plan a budget, purchase high end Vogue patterns, and make trips to Solo Serve for the cheapest fabric.

Every day for several weeks until our family's road trip moving to the San Francisco Bay Area, I labored to coordinate skirts, blouses, dresses, and jackets; the dining room table became my cutting board; my bedroom a sewing room in a constant assembly line. I kept at it until they sold the dining room table out from under me, along with every other stick of furniture and household goods we’d owned.

Now with a suitable wardrobe of old and new handsewn garments in my suitcase stowed in the back of the station wagon, I was traveling as fast as Dad could drive the entire family to California, only to leave for Chicago a few weeks later.

It seems my new life was to begin stitch by stitch.

The one dress I lavished the most time and attention in creating and stitching was my train dress; I would take the California Silver Zephyr from San Francisco to Chicago by coach, two days and two nights aboard. The dress had to be sturdy enough to last while seated in coach night and day.

And it had to be clearly recognizable for the family who was to meet me in Chicago's Union Station where I was to be their “mother’s helper.” I was to live off campus as a day student and be a maid of all work to a wealthy family, the Sterlings, vetted and managed by the nuns to pay for my room and board.

My pride and joy, it was a cotton, princess shirtdress with an open collar, fitted seams at the waist, a full skirt, navy blue with white polka dots, and a wide, red, grosgrain ribbon with a bow at the collar and ties that hung to the hem of the dress. Dramatic, easy-to-wear, and fun—what better way to arrive in the Midwest than in a sassy, red, white, and blue dress.

Standing on the train platform set in the golden grasses of late summer in the San Francisco South Bay station, I gave farewells to my family, hugging and waving. How incredible it was to watch the sunset in the mountain passes of the Sierra from the observation car of the Zephyr and see the moon rise over the barren Nevada desert. My eyes were full of the natural beauty of our nation going cross country by train. Almost too soon, I debarked at Chicago’s Union Station.

"There she is!" red-headed Georgie shouted to his dad. "She's wearing a blue dress with dots and a big red ribbon."

"Wrapped up just like a present." Mr. Sterling, a stocky man in a gray suit, greeted me and shook my hand with a firm grip in the steam and noise of the multi-track platform.

###Chapter Four, to be continued

PROMPTS

Follow along the heroine’s stages together with a notebook—digital or written—or a portfolio for illustrations, photographs, a collage, poster, story board, road map, or a game. The creative possibilities are endless as we explore the fairy tale heroine’s epic journey in our own way and for our time.

Was there a time in your life when you had to escape, take a risk, and leave stifling convention behind? Describe your transitional phase. How did it feel? What happened?

Is there a character in fiction or a woman in real life who inspired you with her courage to take a different path?

Why do think there is such resistance to women living outside past traditions, being true to themselves?

Thanks to all the subscribers who’ve signed up for my interactive book on the Fairy Tale Heroine! I appreciate your subscriptions and those who follow my posts. I look forward to your comments!

Hi Kate, what I really enjoyed about this piece was the way you described and then gave two great examples of fleeing to survive before sharing your own experience. Also, the questions posed at the end for us to reflect upon are really helpful. I’m looking forward to your next installment.

Yes! Love reflecting on this stage as I take a solo trip to the desert wilderness.